|

The library was designed to be very modular and extensible. The logging library supports both narrow-character and wide-character logging. Actually, the two methods of logging are implemented independently (i.e. there are different instances of logging cores for each character type and, therefore, a separate processing pipeline for each character type), so the user will probably want to decide which one he will use. Both narrow and wide-character versions of the library provide similar capabilities, so through most of the documentation only the narrow-character will be described. The library provides configuration facilities to compile only the version of the library that's needed.

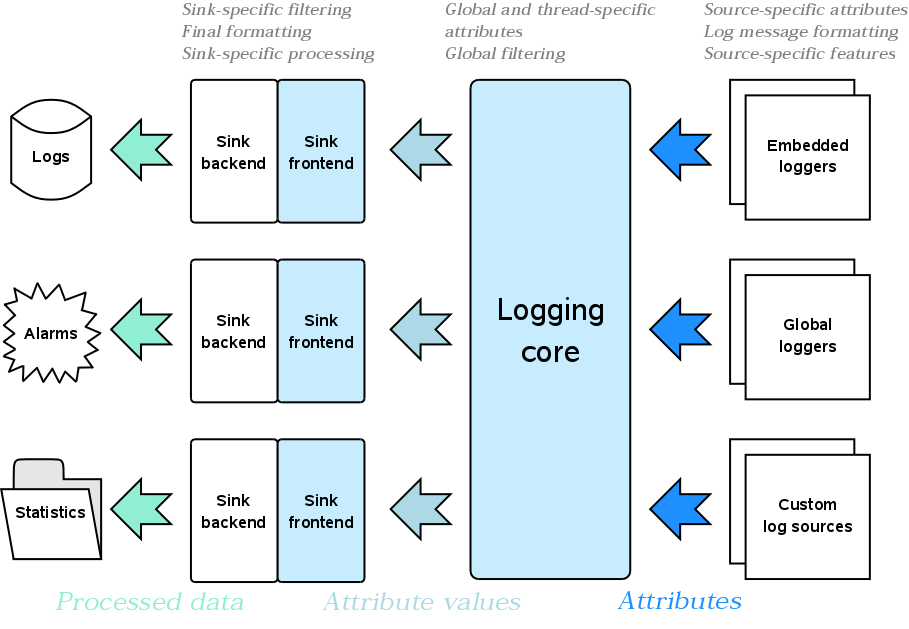

The library consists of three main layers: the layer of log data collection, the layer of processing the collected data and the central hub that interconnects the former two layers. The design is presented on the figure below.

The arrows show the direction of logging information flow - from parts of your application at the right to the final storage, if any, at the left. I say "if any" because the result of log processing may include some actions without actually storing the information anywhere. For example, if your application is in a critical state, it can emit a special log record that will be processed so that the user sees an error message as a balloon tool-tip over the application icon in the system tray and hears an alarming sound. This is a very important library feature: it is orthogonal to collecting, processing logging data and, in fact, what data logging records consist of. This allows use of the library not only for classic logging, but to indicate some important events to the application user and accumulate statistical data.

Getting back to the figure, in the right side your application emits log records with help of loggers - special objects that provide streams to format messages that will eventually be put to log. The library provides a number of different logger types and you can craft many more yourself, extending the existing ones. Loggers are designed as a mixture of distinct features that can be combined with each other in any combination. You can simply develop your own feature and add it to the soup. You will be able to use the constructed logger just like the others - embed it into your application classes or create and use a global instance of the logger. Either approach provides its benefits. Embedding a logger into some class provides a way to differentiate logs from different instances of the class. On the other hand, in functional-style programming it may be more convenient to have a single global logger somewhere and have a simple access to it.

Generally speaking, the library does not require the use of loggers to write logs. The more generic term "log source" designates the entity that initiates logging by constructing a log record. Other log sources might include captured console output of a child application or data received from network. However, loggers are the most common kind of log sources. In any case, in order to initiate logging a log source must pass all data, associated with the log record, to the logging core. This data or, more precisely, the logic of the data acquisition is presented as a set of named attributes. Each attribute is, basically, a function, whose result is called "attribute value" and is actually processed on further stages. An example of an attribute is a function that returns the current time. Its result - the particular time point - is the attribute value.

There are three kinds of attribute sets: global, thread-specific and source-specific. You can see in the figure that the former two are maintained by the logging core and thus need not be passed by the log source in order to initiate logging. Attributes that participate in the global attribute set are attached to any log record ever made. Obviously, thread-specific attributes are attached only to the records made from the thread in which they were registered in the set. Source-specific attribute set is maintained by the source that initiates logging, these attributes are attached only to the records being made through that particular source. When a source initiates logging, attribute values are acquired from attributes of all three attribute sets. These attribute values then form a single view of named attribute values, which is processed further. As you may notice, it is possible for a same-named attribute to appear in several attribute sets. Such conflicts are solved on priority basis: global attributes have the least priority, source-specific attributes have the highest; the lower priority attributes are discarded from consideration in case of conflicts.

When the set of attribute values is composed, the logging core decides if this log record is going to be processed in sinks. This is called filtering. There are two layers of filtering available: the global filtering is applied first within the logging core itself and allows quickly wiping away unneeded log records; the sink-specific filtering is applied second, for each sink separately. The sink-specific filtering allows directing log records to particular sinks. Note that at this point it is not significant which log source emitted the record, the filtering relies solely on the set of attribute values attached to the record.

If a log record passes filtering for at least one sink, the record is considered to be consumable. This is the point when log message formatting takes place. The formatted message, along with the composed attribute values view, is passed to the sinks that accepted the record. As you may have noticed on the figure above, sinks consist of two parts: the frontend and the backend. This division is made in order to extract the common functionality of sinks, such as filtering and thread synchronization, into separate entities (frontends). Sink frontends are provided by the library, most likely users won't have to re-implement them. Backends, on the other hand, are one of the most likely places for extending the library. It is sink backends that do the actual processing of log records. There may be a sink that formats the attribute values and the log message and stores it into a file; there may be a sink that sends log records over the network to the remote processing center; there may be the aforementioned sink that puts record messages into tool-tip balloons - you name it. The most commonly used sink backends are already provided by the library.

Along with the primary facilities described above, the library provides a wide variety of auxiliary tools, such as attributes, support for formatters and filters, represented as lambda expressions, and even basic helpers for the library initialization. You will find their description in the Detailed features description section. However, for new users it is recommended to start discovering the library from the Tutorial section.